Industrial Fiction: Part 1. The Lobby | All scenes

A new work of industrial fiction

Embedded agency is an organizing theme behind most, if not all, of our big curiosities.

It seems like a central mystery underlying many concrete difficulties.

Scene I.

Z still had an hour to wait.

She scanned the cavernous lobby. The surrounding walls were like molten rivers standing still. Thick sheets of aloof concrete, protecting Z from the climate outside.

In the corner Z spotted the now familiar B Code, its shape—with its curves and simple lines—trying too hard to be considered art deco. The lobby-based B Code was substantial yet submissive, stationed quietly in the corner. Z remembered when they were a novelty a decade ago. Had it been that long?

The day they embedded the B Code into the concrete, everything changed.

A descendant of the bar code, and then the QR code, the B Code communicated a localized story. Narratives of the first pour. Specks of maintenance. Opportunities for renewal.

Once smartphones achieved enlightenment-- about a decade ago-- it was hard to dispute their usefulness. Quickly the sensors of disparate “phones” worked to prove themselves. They recorded imperfections in the below and sideways concrete, and they told stories of the quality of systems embedded within… much to the chagrin of the ultrasonic plumbing industry.

Smartphones were the early storytellers of the B Code.

But the B Code contained the story.

The day it all changed, cement was just over 3% of global GHG emissions. GHG, greenhouse gas. It seemed small at first, but that was more than the global aviation industry on a gambling frenzy in Las Vegas. Or Macau. Cement was a hard 3%+. The kind that took more hand waves than purse strings to overcome.

The day they embedded the B Code, the government changed its approach. Some said it was geriatric. That switch from “I care too much about what people think of me” to “I don’t care at all! Let me throw scarves in the air and sing reflective songs at the top of my lungs!”

A joke! of course. But Z knew that.

The real reason the government embedded the B Code was quite obvious. Doing so made THEIR jobs easier. It was much easier to procure and manage with the B Code in place than without it. So what was the harm in that?

Her heartbeat continued to pound. Thud. Thud. Thud. She still couldn’t believe why she was there.

Scene II.

Z had been one of the few to articulate the importance of concrete relative to climate change well over a decade ago. As an anthropologist primed to share the stories of the built environment she had narrowed in on concrete early on. Concrete was historical. Societal. Cultural.

It was also immensely carbon intensive.

Z brushed away at her goosebumps. A draft flowed through the open lobby with an empty, whirring stillness. Her thoughts turned to her past life studying low carbon concrete.

Not many people cared at first. Such a ubiquitous material, overlooked.

Even back then, education efforts had been underway for some time. Forums pulled voices together from architecture, engineering, and construction communities. Structural engineers debated the merits, reminding each other of their trade. Contractors spiraled in internal initiatives. Big concrete and cement companies joined in turn. But in those days, it was just more of the same. Using yesterday’s tools to address today’s problems.

What was the framework again? It wasn’t catchy per se, but the mnemonic helped. She knew it by heart once upon a time.

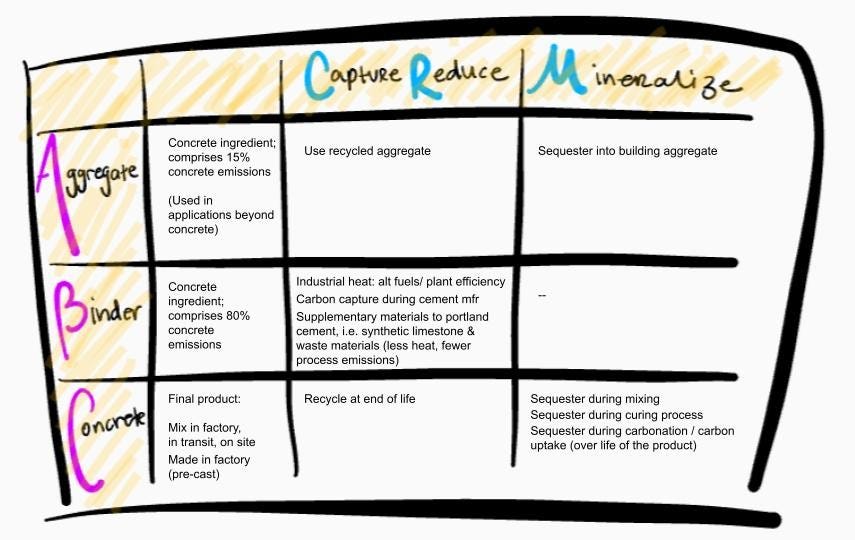

ABC x CRM

Aggregate. Binder. Concrete x Capture. Reduce. Mineralize.

Back then, Z had been accustomed to repeating the words over and over. Sang it as a song. A succinct mantra that reiterated the landscape to herself and to others.

ABC: Aggregate, Binder, Concrete. First there were the aggregates. That crumbly filler. Crushed rock, gravel, sand. Next came the binder--cement and water--acting as a cohesive glue. Mixing brought it all together. Aggregates, meet Binder. Binder, meet Aggregates. Once it was poured, the right temperature, moisture, and time enabled the composite substance to cure and render itself concrete, full of strength and durability.

“Concretus,” to grow together.

In the early 1800s Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) stepped into the limelight, taking over as Premier Binder for Centuries. Made of limestone under heat of kiln and some added raw materials, the residual clinker was then ground into a fine powder. Limestone (CaCO3) with heat results in calcium oxide (CaO) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Ordinary PC was the perfect stage name for this pervasive powder. So ordinary a name that it fell behind the scenes-- wielding its immense power (and escaped emissions) over the globe in stealth.

In her old life, this was where Z came in. There were several opportunities to change concrete’s course as a significant emissions contributor.

Z visualized the matrix she used to describe the opportunity to those who inquired.

Each combination of the matrix had pros and cons. There were different levers to pull, in tradeoff of emissions, durability, strength, and workability. The choice of a solution in one stage impacted the outcomes of another.

Back to the mantra.

CRM: Capture, Reduce, Mineralize. Carbon dioxide released during the production of clinker could be captured at the source, with prospects for further utilization. There were also opportunities to reduce emissions for both ingredients, the aggregate and the binder. For example, recycled concrete could be used as aggregate in place of freshly mined rocks. Alternative fuel sources could be used to heat the cement kilns. And supplementary sources to portland cement reduced or even avoided the direct impact of clinker emissions entirely.

Then there was mineralization.

That’s where things got exciting. Z cracked her knuckles. In addition to point source carbon capture and avoidance, concrete had the superpower to also sequester carbon dioxide within.

The first opportunity was embedding CO2 into building aggregate. It seemed almost too simple at the time, and perhaps it was. These new synthetic rocks were competing against literal dirt! Despite their underdog stature, mineralized aggregates were persistent little things— resolute chunks of former CO2 that could be tucked permanently away as they strengthened the world’s infrastructure.

The second opportunity was sequestering carbon dioxide into the composite itself, during either the concrete mixing or curing stages. Whether added directly to the mix or used to cure pre-cast units, injected streams of CO2 danced with the nubile concrete in full force. Each technology had its own preference for where best to introduce itself into the process.

Z had to remind herself of those early days. That was the time before direct air capture became so ubiquitous. For sequestration of ingredient or final product, most technologies back then relied on pure sources of CO2 for their mineralizing efforts. The purification required was just one more step; it constrained supply. It was even rumored that some of the biggest cement companies hustled with the likes of Coca Cola and AB InBev to get their hands on the purest batch.

Last but not least was the most surprising opportunity of them all-- carbon uptake over the life of the structure. Concrete accumulated CO2 over time, years after its first mix and pour. It certainly was the slowest option but researchers aimed to speed it up. It boggled the mind that just with time more atmospheric CO2 could be extracted.

Compounding always confused people.

In those early days, it wasn’t clear which new technology or set of solutions would win out. Or even which set of policies would.

Z had spent time with each of them. They weren’t just business models, technologies, or regulatory frameworks, no. There were people behind those things. She knew what made them tick. Their org structures, methods for decision making, the landscape into which each placed their tech and advocacy.

In the mid 2020s, it had become popular for yuppies and the like to back new technologies. Low carbon concrete was suddenly all the rage. Even though thrilled, Z never quite understood why. Maybe because its use, in a time of uncertainty, was so certain. Every growing city and country needed concrete. Global building stock was projected to double over the next forty years. The option to reduce and remove carbon emissions from so many angles made concrete so appealing. Diversified yet focused at the same time. (Plus, it didn’t require consumers to change their day to day behavior.)

This new wave of interest in low carbon concrete changed the game; attention and sense of identity expanded from industrial corporates to the consumer. It was like an orbital jump from the slower pace layers of infrastructure to the frenetic action of commerce and fashion. Everyone could buy a permanent slice. Carbon negative contributions became the status symbol people appended to their name, like the former squiggles of a PhD or MBA.

Demand had pulled them all forward. And it was exciting!

New R&D finally got funded. Promising technologies ramped up deployments. Contractors could get low carbon certified, their personalized certificates following them wherever they went. Eventual breakthroughs in direct air capture only accelerated progress.

Best yet: more people entered the field. Z started to have colleagues!

Despite all of this, something was off. Collectively they had reduced costs for the first stage of deployment, but... Costs were still too high. Risk aversion, too concerning. And global lessons transfer remained too limiting.

What soft infrastructure was holding them back? It plagued Z.

And then the B Code changed all of that.

工

Please note: This series reflects my own learning of the industry and may contain incorrect information. I use this writing as a method to educate myself, set up frameworks, and highlight areas where my understanding can be improved. Which means, it’s perfect fodder to then discuss with the experts! I plan to update this series over time in hopes that the learning process is useful to my readers, too.